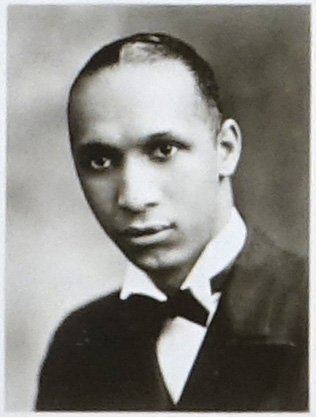

Harold Lindsay Tutt was born on 10 December 1903 to Ryle Tutt and Minnie Wynn, in Higbee, Missouri. A member of Alpha-Nu Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha while at ISC, Tutt was a fraternity brother of John “Jack” Trice. At the start of October 1923, Tutt was the newly appointed Alpha Nu Chapter Correspondent to The Sphinx, looking forward to a banner year, unsuspecting of the tragedy to come: the death of Brother Trice on 8 October of that year (Tutt, 1923). Within the coming weeks, Harold had alerted Cora to the dire health of her injured husband (Greene, 1988); joined the funeral party that accompanied Jack’s remains to Hiram, Ohio, for burial; helped to organize the program for the African American community’s memorial service at the home of Mr. and Mrs. E. L. Gater in Ames on 21 October; and reported to those assembled on the campus memorial service and the Ohio burial service (“Tribute Is Paid,” 1923).

The Alpha-Nu Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha expressed condolences when Tutt’s father passed away in January of 1925 (“Alpha Nu Chapter, Des Moines, Iowa,” 1925), and by the time of the Iowa Census that year, Harold was rooming at 2522 Chamberlain Street, the Ames home of his grandmother, Louise Wynn, mother-in-law of the home’s owner, Arthur Marshall. Living with them in 1925 were Tutt’s fellow ISC students Holloway Smith, the second African American football player at ISC; Benjamin Crutcher; and Thomas Whibby.

Tutt left ISC before graduating and completed his college career at Michigan State College (MSC; now Michigan State University) in 1927. There he sought a degree in physical education, not completing it due to the death of his fiancee (“The Onlooker,” 1951). He went on to work in Lansing, MI, as a porter in Al and Paul’s shop and, before that, The Looking Glass barber shop. According to the MSC alumni magazine, he was well-known in the community for his tutoring of African American youths at the college and coaching of Lincoln Community Center sports teams in basketball, softball, and baseball, among others. (“Necrology,” 1951).

As the Lansing State Journal reported upon his death, “[Harold Lindsay] Tutt became known as a gentleman’s gentleman and earned the affection of all races and creeds” (“The Onlooker,” 1951, p. 46). When he passed away on 15 April 1951, at St. Lawrence Hospital in Lansing, Michigan, his death was mourned by many members of the Lansing community, Black and White alike, because Tutt was such a likable man. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Lansing (Find a Grave, 2012).

Sources

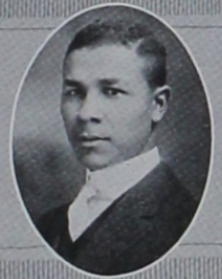

Photo credit: Alpha Nu chapter State College of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. (1923, June). The Sphinx, 9(3), p. 17. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192300903

Alpha-Nu chapter, Des Moines, Iowa. (1925, Feb.). The Sphinx, 11(1), p. 40. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192501101

Find a grave [database and images]. (2012, Mar. 14). Memorial page for Harold Lindsay Tutt (1903–1951), Find a Grave memorial ID 86762358. Retrieved from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86762358/harold-lindsay-tutt. Maintained by JLL (contributor 47314524).

Necrology. (1951, June 1). The Record. p. 13. Michigan State College. Retrieved from https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/162-565-904/19510601sm.pdf

The onlooker. (1951, Apr. 19). Lansing State Journal, p. 46. Newspapers Online. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/clip/14055947/lansing-state-journal/#

Tribute is paid to late football star: Negroes honor dead in fitting memorial service. (1923, Oct. 22). The Ames Daily Tribune and Ames Evening Times, p. 1. Newspaper Archive. Retrieved from https://newspaperarchive.com/ames-daily-tribune-and-ames-evening-times-oct-22-1923-p-1/

Tutt, Harold L. (1923, Oct.). Alpha Nu chapter, Des Moines, Iowa. The Sphinx, 9(4), p. 3. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192300904