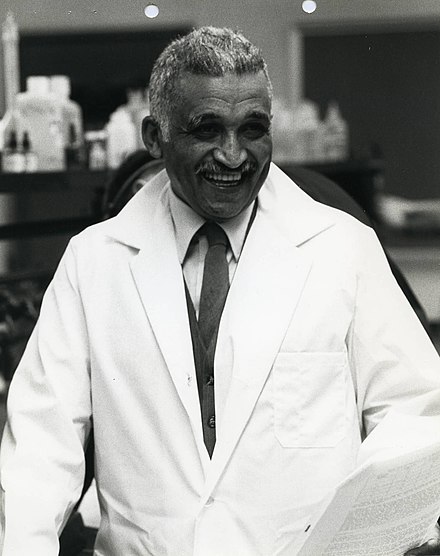

John “Jack” G. Trice was born 12 May 1902 in Hiram, Ohio, to Green Trice, a farmer, and Anna W. Trice. When Jack entered Iowa State College in January 1922, he was enrolled in a two-year non-collegiate Agricultural program so that he could obtain the necessary credits in missing preparatory classwork to enter the Animal Husbandry degree program. He attained that goal in Summer 1923 after a strong performance in his preparatory courses. Trice was active in the the Alpha-Nu Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha in 1923, belonging alongside Iowa State brothers A.C. Aldridge, J. R. Otis, F. D. Patterson, L. A. Potts, J. L. Lockett, J. W. Fraser, and R. B. Atwood (Aldridge, 1923).

In Fall 1923, Trice’s transcript notes that he “Dropped” his 15 1/3 credits of coursework on 9 October 1923. What that transcript note doesn’t say is that Trice’s credits were dropped because Jack, an athletic standout and the first African American member of the Iowa State football squad, had died on 8 October 1923 after injuries sustained in the October 6th Iowa State-University of Minnesota football match-up in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Iowa State College Department of Hygiene issued a statement concerning Trice’s official cause of death, attributing it to “Traumatic Peritonitis, following injury to abdomen in football game” (quoted in Schwieder, 2010, p.39). The tragedy of this event is compounded by the aspirations and pride expressed by Trice’s fraternity brothers. Brother A. C. Aldridge, writing for the fraternity’s journal, The Sphinx, in June of 1923, only months before Trice’s death, praised Trice’s abilities as an all-around athlete and his potential to be one of the athletic greats:

Among the new brothers that have filled the ranks of Alpha Nu is brother John Trice, who is destined to reach great heights in the athletic world. Winning his numerals in football last fall, did not satisfy Brother Trice. This spring, his work on the “Prep” track squad was a revelation to the most keen fans of that sport. He has frequently thrown the discuss (sic) one hundred and thirty-five feet and passing the forty foot mark with the shot, seems to be an easy matter with him. Trice has not only shown ability on the track and gridiron, but his aquatic habits have obtained for him membership to the Iowa State College Lifesaving Corps. (Aldridge, 1923).

Indeed, Jack had won the shot put event in the Missouri Valley Conference meet as a freshman in 1922 . He’d also been a solid academic performer, with average grades of 93 (Tutt, 1923b).

Jack Trice’s memorial service on central campus at ISC, on 9 October 1923, was attended by several thousand people, according to news reports, no small number for a school with slightly over 3,000 students (Schwieder, 2010). The African American community of Ames held its own memorial service, organized by Jack’s fraternity brothers, on Sunday, October 21, at the home of Mr. and Mrs. E. L. Gater (“Tribute Is Paid,” 1923). Money was collected at each event to help cover funeral expenses and to transport Jack’s body to Ohio. On the trip back to Hiram, Trice’s wife, Cora; his mother, Anna; and others from ISC, were accompanied by Trice’s fraternity brother Harold L. Tutt (Schwieder, 2010). John G. “Jack” Trice is buried in Fairview Cemetery in Hiram, Ohio.

Following Trice’s death, his teammates on the 1923 ISC football squad installed a bronze plaque in the Iowa State College gymnasium bearing the words of Jack’s last letter, found in his coat pocket after he passed (Tutt, 1924). The December 1923 edition of the fraternity’s national magazine, The Sphinx, was dedicated to Brother Trice’s memory (The Sphinx, 1923).

In October 2023, a posthumous Bachelor’s of Science Degree in Animal Husbandry was conferred upon John “Jack” Trice by Iowa State University President Wendy Wintersteen. This degree conferral occurred as part of the culmination of the year-long Jack Trice 100 Commemoration, a series of events intended to honor Jack’s brief life and his enduring legacy. The Jack Trice 100 kicked off in October 2022 with a ceremony, the dedication of Jack Trice Way (the section of S. 4th Street between University Boulevard and Beach Avenue, adjacent to the entry to the Jack Trice Stadium complex), and the installation of the sculpture “Breaking Barriers” (sculptor Ivan Toth Depeña, American, b. 1972) in the Albaugh Family Plaza north of Jack Trice Stadium. Throughout the year, lectures, art installations, and historical exhibits, among other events, marked the centennial of Jack’s death.

Sources

Photo Credit: Photo of Alpha-Nu chapter State College of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. (1923, June). The Sphinx, 9(3), p. 17. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192300903

Aldridge, A. C. (1923, June). Alpha Nu chapter State College of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa. The Sphinx, 9(3), p. 17. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192300903

Greene, Cora Mae Starland Trice. (1988). Cora Mae Trice Greene letter to David Lendt, August 3, 1988, p. 3. Iowa State University Library Digital Collections. Retrieved from http://n2t.net/ark:/87292/w9n872z9b

In memoriam. (1923, Dec.). The Sphinx, 9(5), p. 2. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192300905

Schwieder, D. (2010). The life and legacy of Jack Trice. The Annals of Iowa 69(4), p. 379-417. doi: https://doi.org/10.17077/0003-4827.1474

Tribute is paid to late football star: Negroes honor dead in fitting memorial service. (1923, Oct. 22). The Ames Daily Tribune and Ames Evening Times, p. 1. Newspaper Archive. Retrieved from https://newspaperarchive.com/ames-daily-tribune-and-ames-evening-times-oct-22-1923-p-1/

Tutt, Harold L. (1923a, Oct.). Alpha Nu chapter, Des Moines, Iowa. The Sphinx, 9(4), p. 3. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192300904

Tutt, Harold L. (1923b, Dec.). Alpha Nu chapter, Des Moines, Iowa. The Sphinx, 9(5), p. 28. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192300905

Tutt, Harold L. (1924, June). Alpha-Nu chapter, Des Moines, Iowa. The Sphinx, 10(3), p. 17. ISSUU. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/192401003